By the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

Understand Behavioral Finance Fundamentals: Grasp the core principles of behavioral finance and how it differs from traditional financial theories.

Identify Psychological Influences on Decision-Making: Recognize the role of cognitive and emotional factors in shaping investment behavior.

Appreciate the Human Element in Markets: Explore how investor psychology creates inefficiencies in financial markets.

Lay the Groundwork for Identifying Biases: Establish a solid foundation for recognizing specific cognitive biases that influence investment decisions in the next lesson.

Money may not buy happiness, but it certainly buys complexity—especially when it comes to how we think and act around it. Behavioral finance dives deep into the intricate relationship between human psychology and investing, unraveling why we often make decisions that defy logic and harm our financial outcomes.

Imagine this: You’re at a casino. You’ve just lost $500, but you convince yourself that doubling down will help you recover your losses. The rational approach would be to cut your losses and walk away. But your emotions, the thrill of the chase, and the fear of “being wrong” cloud your judgment. Welcome to behavioral finance—a field that explains why we make such decisions, even when logic screams otherwise.

In this lesson, we’ll uncover how our brains, emotions, and behaviors shape our financial lives, setting the stage for deeper insights into the traps we fall into and how to avoid them.

Behavioral finance is a field that blends psychology and economics to explain why investors often make irrational decisions. Unlike traditional finance, which assumes humans are logical and always act in their best financial interest, behavioral finance acknowledges that we are emotional beings prone to mistakes.

It challenges the “homo economicus” model—the idea that humans are perfectly rational decision-makers. Instead, behavioral finance introduces the concept of bounded rationality, which states that our decisions are influenced by limited information, time constraints, and mental shortcuts (heuristics).

To understand behavioral finance, we must first explore how our brains work. Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, a pioneer in the field, introduced the concept of System 1 and System 2 thinking in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow:

System 1: The Fast, Emotional Thinker

This is our gut reaction—the part of the brain that makes snap judgments based on intuition and emotion. System 1 is great for quick decisions but prone to biases and errors.

System 2: The Slow, Analytical Thinker

This is the logical, deliberate part of our brain that takes time to analyze information and make reasoned decisions. While more accurate, System 2 is slower and requires effort.

In investing, these two systems often collide. For example, your System 1 might panic and sell a stock during a market downturn, while your System 2 urges you to stay calm and think long-term. Behavioral finance helps bridge this gap, encouraging more System 2 thinking in financial decision-making.

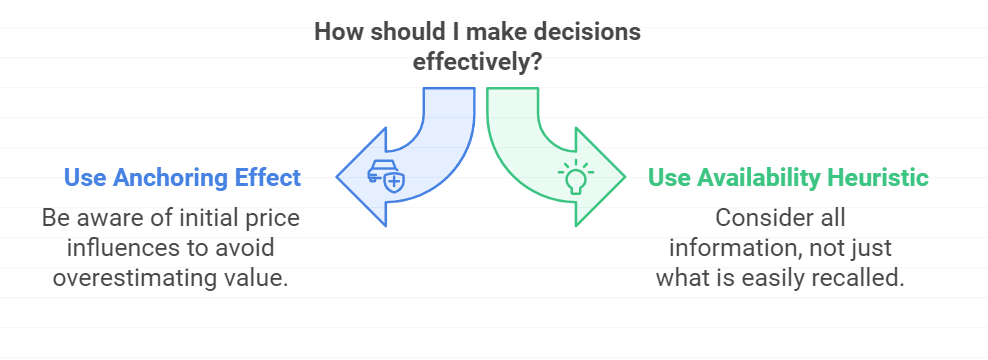

Heuristics are mental shortcuts we use to simplify complex decisions. While they save time and effort, they often lead to errors in judgment.

Anchoring Effect

Imagine you’re buying a car. The salesperson quotes $50,000, but then offers a “discounted” price of $45,000. The original price anchors your perception, making the discount seem like a great deal—even if the car is overpriced.

In investing, anchoring might cause you to hold onto a stock because of its past high price, even when current market conditions suggest selling.

Availability Heuristic

This is the tendency to base decisions on easily recalled information rather than comprehensive analysis. For instance, if you hear about a friend making a fortune in cryptocurrency, you might overestimate your chances of success and jump in without proper research.

Two emotions dominate the financial markets: fear and greed. These emotions can drive markets to extremes, creating bubbles during times of greed and crashes during periods of fear.

Fear

Fear leads to risk-averse behavior, causing investors to sell assets during downturns or avoid potentially profitable opportunities due to perceived risk.

Greed

Greed pushes investors to chase high returns without assessing the risks. This often happens during speculative bubbles, where prices rise rapidly based on hype rather than fundamentals.

A classic example is the Dot-Com Bubble of the late 1990s, where investors poured money into tech stocks with little regard for their actual value.

Humans are inherently social creatures, and this trait often spills over into investing. Herd behavior occurs when individuals mimic the actions of a larger group, even if those actions are irrational.

Why do we follow the herd?

Safety in Numbers: It feels safer to follow the crowd than to take a contrarian stance.

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO): The fear of being left out of a lucrative opportunity drives people to invest without proper research.

While herd behavior can lead to short-term gains, it often results in poor long-term outcomes, as seen in speculative bubbles and crashes.

Behavioral finance provides insights into market anomalies that traditional theories struggle to explain.

Overreaction and Underreaction

Investors often overreact to news, leading to sharp price movements. Similarly, they underreact to gradual changes, such as improving company fundamentals.

Momentum Effect

Stocks that perform well tend to continue doing so in the short term, driven by herd behavior and overconfidence.

The first step to overcoming behavioral biases is recognizing them. Self-awareness allows you to identify when emotions or mental shortcuts are driving your decisions, enabling you to pause and engage System 2 thinking.

Practical tips for increasing self-awareness:

Keep a Trading Journal: Record your decisions and the rationale behind them to identify patterns over time.

Set Rules: Establish predefined rules for buying and selling to minimize emotional influence.

Seek Diverse Opinions: Avoid echo chambers by consulting multiple sources of information.

Behavioral finance reveals that investing isn’t just about numbers—it’s about understanding yourself. By recognizing the psychological forces at play, you can avoid common pitfalls and make more informed decisions.

As we wrap up this foundational lesson, remember that the journey to becoming a disciplined investor starts with understanding your own mind. The biases, heuristics, and emotions we explored today set the stage for the next step: diving deeper into the specific cognitive traps that trip up investors.

In the next lesson, Common Cognitive Biases – Identifying the Traps Investors Fall Into, we’ll take a closer look at these mental pitfalls and learn how to sidestep them to build a more resilient investment strategy. Ready to uncover these traps? Let’s move forward!